From the Soviet Union to the United States

In 1972, as Richard Nixon prepared to visit the Soviet Union, officials at a Leningrad workplace scrambled to impress. The building had only primitive toilets that barely worked, so they rushed to install a single gleaming American Standard model for the delegation. Nixon never came, but the toilet stayed—and quickly became an office attraction.

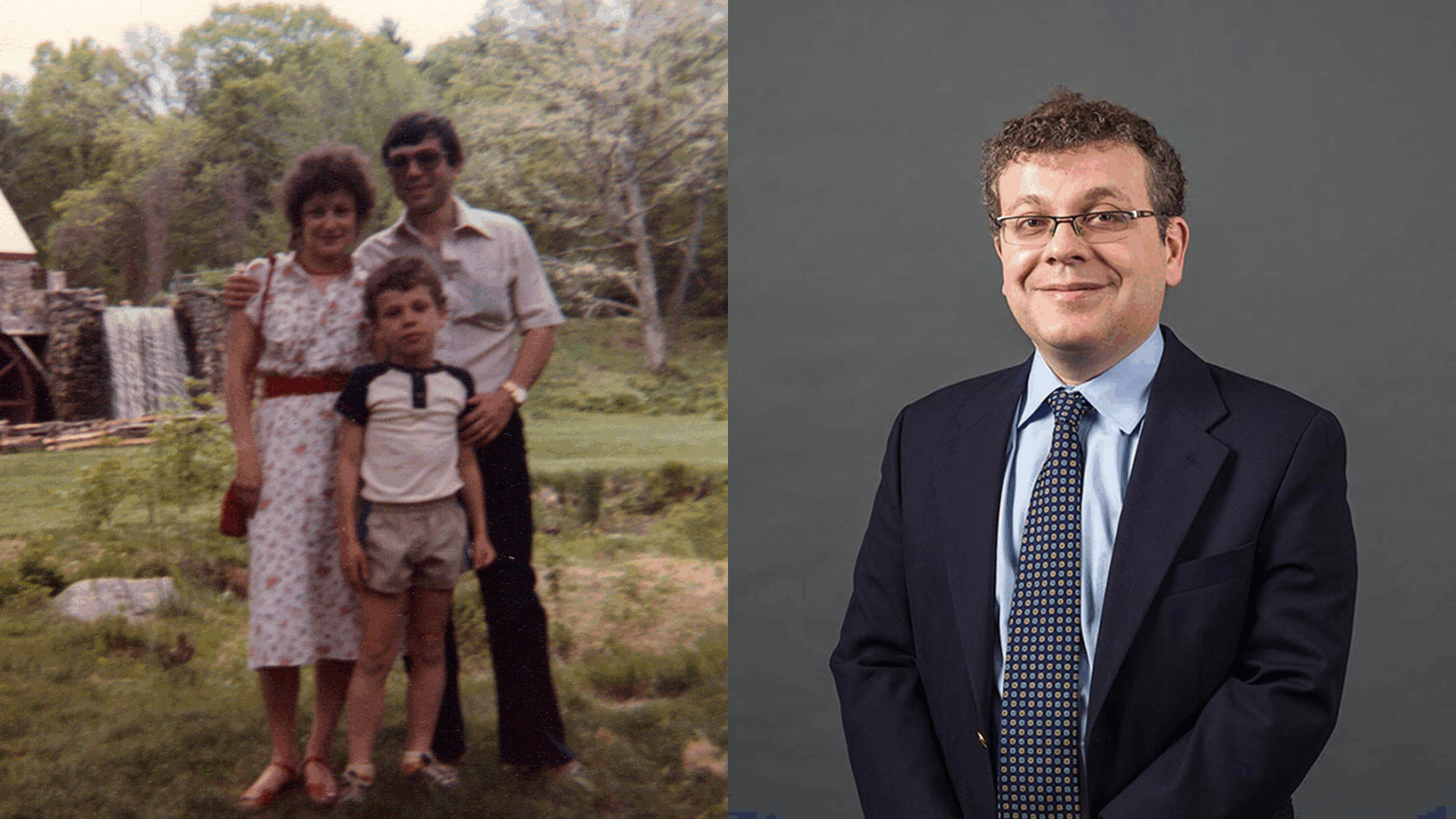

Among those who lined up to see the modern American marvel was Yefim Somin entertaining dangerous thoughts: “I want to live in a country where this is standard.” That toilet was a reminder that there seemed to be at least one country out there where people did not have to line up or wait for the state officials to decide whether they deserve the basic comfort and dignity afforded by human innovation. Maybe, too, it could be a place where his children would not grow up under the shadow of the secret police or hide who they are. A place where they could simply be free.It was by no means easy or risk-free. But in 1979, Yefim finally got his wish—bringing with him his wife and his five-year-old son named Ilya.

Ilya grew up in America, shaped by his parents’ memories of life under Communism. He would spend his life studying the ways freedom can be eroded when governments overstep their bounds. In 2025, that calling put him in courtrooms, challenging the President of the United States over sweeping tariffs imposed under emergency powers. (The Supreme Court has put the case on an expedited track, with oral arguments scheduled for November.)

The principle at stake was the same one that had once driven his family to leave: government has no business deciding who gets to enjoy the ordinary fruits of freedom. And yet, in America, tariffs had just become a familiar tool for doing just that—shifting costs, distorting markets, and presuming to know better than the people themselves. In a truly American story, the child who once left a system of government propaganda and permission became the scholar who stood up in court to remind Americans of their own first principles. One of the cases that gave him that chance began with a small business near Lake Erie.

FishUSA and the Tariff Challenge

FishUSA, which started in a Pennsylvania garage and grew into one of the nation’s largest fishing retailers, was hit hard by Trump’s sweeping tariffs in 2025. An American business built on affordability and access was suddenly punished by a government that presumed to know markets better than those who built them. FishUSA and four other businesses challenged the tariffs as exceeding presidential authority under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act. By August 2025, they had prevailed—twice. Both the Court of International Trade and Federal Circuit found Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariffs “unbounded in scope” and beyond constitutional limits.

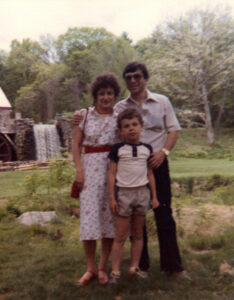

A key figure in that legal challenge has been George Mason University and long-time IHS alum law professor Ilya Somin. The case itself began when his blog post outlining possible arguments against the legality of the tariffs caught the eye of Jeff Schwab of the Liberty Justice Center. Somin joined forces with LJC and other attorneys, representing the plaintiffs and helping craft the arguments that ultimately persuaded the courts.

But while the tariff case put him in the courtroom, Somin is best known as a writer and teacher. He has spent much of his career exploring how freedom works in practice—through migration rights, property rights, federalism, and the limits of voter knowledge. In Free to Move: Foot Voting, Migration, and Political Freedom (Oxford University Press), he makes the case for mobility as a form of political choice, while in Democracy and Political Ignorance (Stanford University Press) he examines why smaller government can be smarter in a world where most citizens can’t follow every issue in detail. Beyond academia, his work has been featured in major outlets, including the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Atlantic.

Ilya Somin and the Institute for Humane Studies

Somin’s academic interests grew out of his awareness of both the fragility and the sanctity of freedom, which made the mission of the Institute for Humane Studies a natural fit. “When I was in law school, IHS helped me pay some of the tuition at a time when I didn’t have much money,” he recalled. Over the years, he went on to speak at IHS seminars, and at one such event in 2008, met his future wife, herself an IHS alum. They later had two children. “In that respect,” Somin says, “IHS had a huge impact on my life, and I’m very grateful.”

For Somin, the value of IHS lies in helping students at the moment when they’re forming their intellectual paths. “IHS can have the biggest impact by reaching people when they’re young—18 to 25—through in-person seminars and networks that make ideas tangible,” Somin said. “That’s when views and careers are most open to change.”

Today, Somin teaches at George Mason University and continues to give back by speaking at IHS seminars, helping shape the next generation of scholars. His story illustrates why IHS exists: to defend the ideas that make freedom possible—for a boy in Leningrad, for entrepreneurs in Pennsylvania, and for anyone who seeks to build prosperity without asking government permission. IHS promotes freedom, not by lobbying or litigating, but by creating spaces where young thinkers turn curiosity into calling, meet fellow scholars, and carry forward the tradition that once shaped their own lives.

Ilya Somin’s story is a reminder that freedom is fragile, but worth defending—in classrooms, in courts, and even in the everyday standards of life that make prosperity possible.

By supporting IHS, you invest in scholars at a formative stage in their careers—not only with crucial financial support, but also with inspiration and connections to other like-minded and driven intellectual collaborators that they can’t find anywhere else.